The recent suggestion by Nigeria’s Honourable Minister of Education that English alone should serve as the language of instruction in schools has reignited a long-standing debate about language policy and educational equity. While the call for a common academic language may appear practical, such a proposal neglects decades of linguistic and educational research showing that excluding local languages in early education undermines comprehension, cognitive development, cultural identity, and inclusion.

Language in education is not simply about communication, it is about cognition, belonging, and justice. The evidence is clear: Nigeria does not need a monolingual policy for progress; it needs a multilingual, layered framework that recognises that local languages are acquired naturally, while English is learned formally. The issue at hand is not prestige, but pedagogy.

International and local research overwhelmingly supports the use of the mother tongue as the primary language of instruction during a child’s foundational years. According to UNESCO (2025), children who begin their education in a familiar language exhibit stronger reading comprehension, greater classroom participation, and more positive attitudes toward learning. The UNESCO Institute for Education (2024) further notes that early education in the home language leads to better academic outcomes, higher retention rates, and reduced dropout levels.

In the Nigerian context, evidence mirrors these global findings. For instance, Ezeokoli and Ugwu (2025) found that parents, teachers, and students in Oyo State strongly believe that using the mother tongue facilitates not only the acquisition of English but also enhances comprehension across subjects and reinforces cultural identity. When learners understand the medium of instruction, they engage more deeply, build confidence, and transition more smoothly into additional languages later in life.

It is crucial for policymakers to recognise a basic linguistic reality: children acquire their mother tongue naturally from birth through interaction with parents, siblings, and the community. In contrast, English is a learned language, requiring explicit instruction, exposure, and practice.

To impose English as the medium of instruction from the very start of schooling is to expect children to learn and learn again, first the language itself, and then the content conveyed through it. This double cognitive load often results in confusion, frustration, and slower progress.

When initial education is conducted in a familiar language, cognitive load is reduced, comprehension improves, and learning becomes meaningful. Only after this foundation is secured can English be taught more effectively. This is precisely what UNESCO (2024) advocates in its “mother-tongue plus” framework, recommending at least six to eight years of home-language instruction before transitioning to English as the dominant medium.

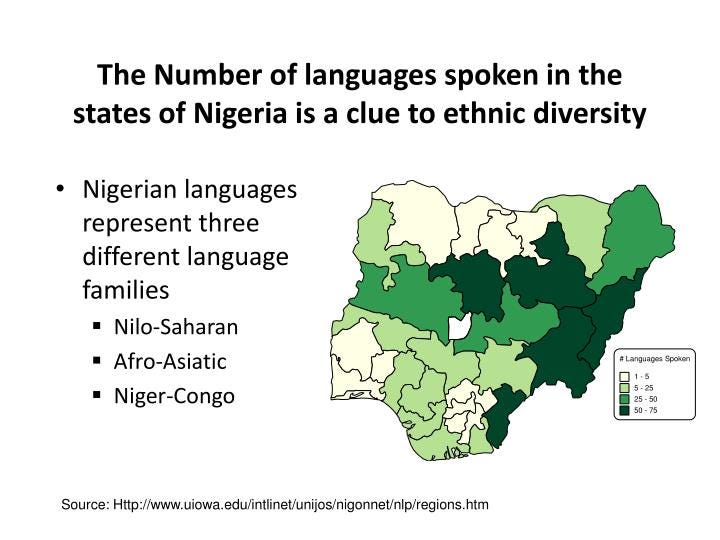

Languages do more than transmit information; they carry the memory, identity, and worldview of a people. Each indigenous language in Nigeria embodies centuries of environmental knowledge, oral tradition, moral philosophy, and social wisdom. When education sidelines these languages, it marginalises the communities that speak them and risks erasing cultural heritage.

Globally, UNESCO (2025) warns that a language disappears every two weeks, often due to neglect within educational systems. In Nigeria, the integration of local languages into schooling is not just a pedagogical necessity but a moral obligation. A study in Ondo State by Akinsola (2025) found that using Yorùbá as a medium of instruction in early education significantly improved students’ bilingual proficiency and reinforced their cultural pride. Eliminating such practices would not only weaken academic engagement but also represent a cultural disservice to future generations.

Policy decisions in education carry far-reaching consequences. A sudden shift toward exclusive English instruction, without adequate preparation, risks undermining decades of incremental progress in inclusive education. Four major dangers stand out:

1. Learning Loss: Young learners struggle to understand lessons delivered in an unfamiliar language, leading to poor comprehension, lower achievement, and increased dropout rates (UNESCO, 2024).

2. Widened Inequity: Students from non-English-speaking homes face disproportionate disadvantage, deepening the educational gap between urban and rural populations (Nwachukwu et al., 2025).

3. Cultural Alienation: Disregarding home languages severs children’s connection to their communities, eroding self-esteem and social belonging.

4. Implementation failure: A national policy without trained teachers, local-language materials, or orthographic standardisation will collapse under its own weight (Akinsola, 2025).

A more sustainable alternative is a phased and resource-rich transition, one that maintains local languages as the medium of instruction in early grades while systematically preparing teachers, materials, and curricula for bilingual or multilingual education in later years.

Rather than imposing a single linguistic path, Nigeria should embrace a multilingual and inclusive education policy that aligns with both national realities and international best practices:

1. Years 1–4 (or 1–6): Teach in the child’s home or community language while introducing English as a subject.

2. Years 5–7 and beyond: Gradually expand English as a medium of instruction while retaining local languages as core subjects.

3. Invest in teacher training, orthographies, and materials development: Teachers need practical resources and pedagogical training to manage multilingual classrooms effectively (Ekeh, 2025).

4. Use digital and print media to promote literacy in local languages.

5. Integrate language and identity into curriculum design, ensuring that cultural content reinforces national cohesion rather than division.

6. Uphold inclusion as a principle, not an afterthought: Multilingual pedagogy enables equitable participation and protects the linguistic rights of every child (Nwachukwu et al., 2025)

Nigeria’s greatest educational strength lies in its linguistic and cultural diversity, not in the uniformity of a single language of instruction. A policy that values only English risks producing learners who can speak but not think deeply, read but not relate, and achieve academically without belonging culturally.

Defending local languages in education is not a rejection of English; it is a recognition of the child’s right to understand, the community’s right to inclusion, and the nation’s duty to preserve its heritage. As UNESCO (2025) observes, language policy in education must balance global competitiveness with local rootedness.

To preserve identity and enhance learning, Nigeria must adopt a multilingual, inclusive, and evidence-based policy, one that empowers children to enter school confident in their language, learn English competently, and grow into citizens grounded in their culture and capable in the world.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily of the organisation TheRadar.

Ministry of Education clarifies proposal on 12-year education system

Meanwhile, TheRadar earlier reported that the Federal Ministry of Education clarified that the Education Minister Tunji Alausa only proposed the introduction of a 12-year basic education system, and there had been no immediate policy change.

The clarification was In response to widespread reports suggesting that the Junior and Senior Secondary School (JSS and SSS) system would be scrapped.